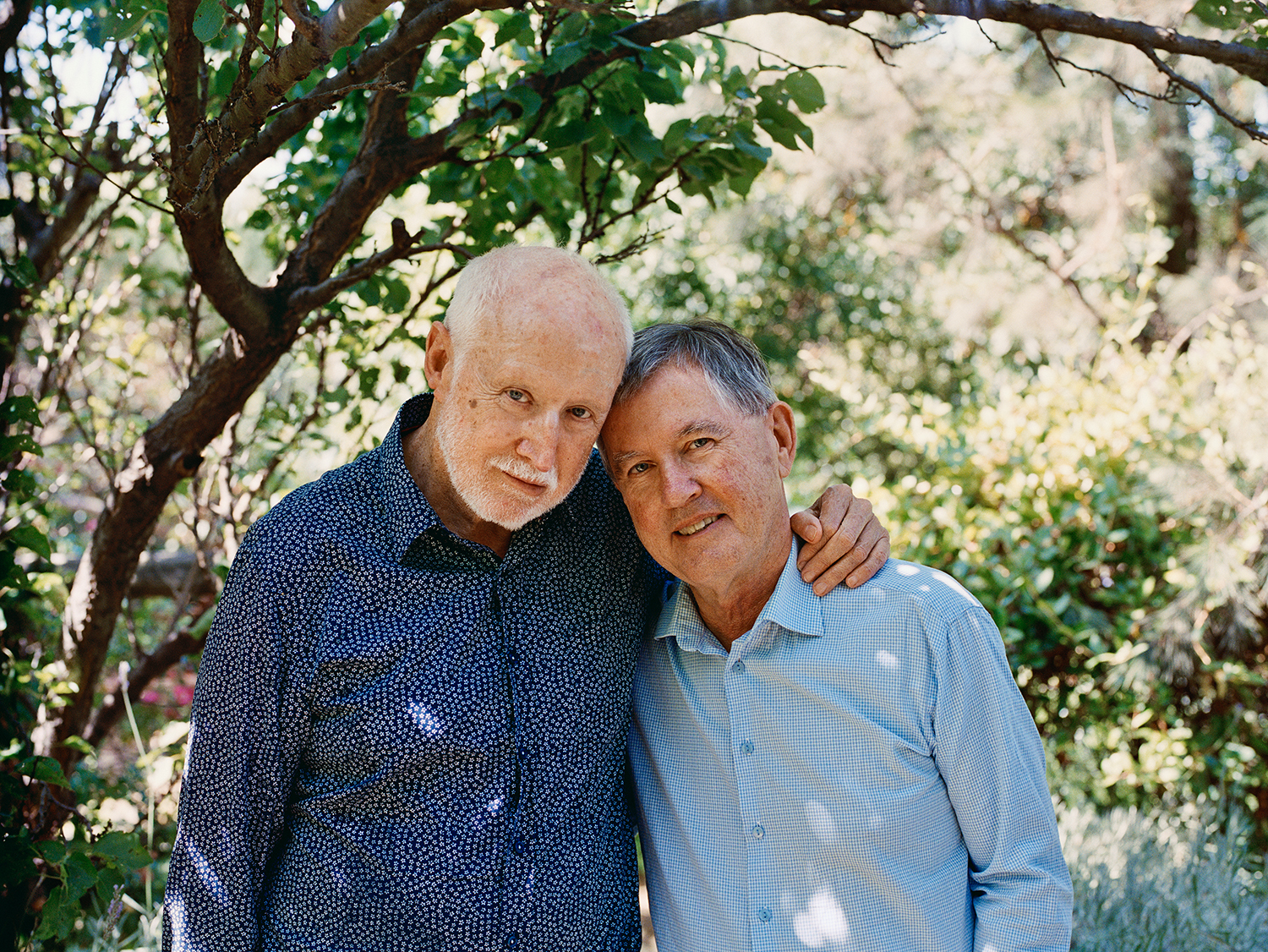

Phillip Siggins & Chris Wheat

DR: how does it feel to be a local in

Castlemaine?

PS: We’re not really local. We're local insofar as we've been here for 20, 22 years – most of that time we had a holiday house because we were living in St Kilda. But we don't regret moving here full time. It's been wonderful.

We did it because I wasn't very well. I got various forms of cancer, one after the other and I’m still on chemo and stuff for a thing called multiple myeloma. So, I couldn’t cope with our St Kilda place. It has massive numbers of steps to get up, so everything's nice and level here. But that wasn’t the sole reason, it was also to retire. Chris had finally left school. He got his certificate for 45 years’ service and then stayed on for another five.

We originally bought this place in 2000 but we didn’t move here until 2018.

DR: Did you know about the gay community here or have friends within that community when you had the holiday house?

PS: Kind of. Well, there’s a sort of Central Highlands set up really. Before this we had a property at Smeaton, and we had some lesbian friends who were very much involved in establishing the Pride Parade and the Chillout Festival. And there were Castlemaine people who came to that and it's all one. Even a little town like Smeaton had quite a gay contingent, didn’t it?

CW: Yeah. And there are connections between Kyneton, Daylesford, Trentham, Newstead, Castlemaine – and people know gay people in each of the towns. Not necessarily well, but there's kind of links that go on.

PS: It really started with Jack's cafe restaurant in Daylesford. We're talking about late 70s, 80s. There was the Harvest Cafe, which wasn't gay, but everyone was completely stoned.

DR: Including you?

P&C: Not really, no. We were more into …

CW: I took drugs when I was in my very early 20s …

PS: Tut tut tut, but mainly we're into high fibre rather than drugs now. So, we all started getting to Jack's Cafe, which was the genesis of the gay world, really, in Daylesford, wasn’t it?

PS: Friday nights at Jack's was extremely funny. There were competitions and that just naturally evolved into Chillout with …

CW: Thousands!

PS: … gumboot throwing and rural pursuits.

CW: Chillout, it's a big thing now.

PS: Huge.

DR: Did you go to that regularly?

PS: Oh, yeah, we went quite a few times.

CW: I was so overworked. I can remember being there – we parked and I sat in the car and corrected year 12 essays.

DR: How has the gay scene or queer scene changed over the last 20 years or so since you've been coming here?

PS: It's evolved massively compared to when we first came here.

CW: Yeah, it has, thanks to The Alluvians really ...

PS: That focused it.

CW: Yeah. You look at the site now and there's things going on the whole year ...

PS: There’s almost too much to go to. There’re games nights and there's car things which I am not that interested in. But there's art things, there’s the sketching group – there’s loads. But also every Sunday they now get together at the Morocco bar, in town, that's on every last Sunday of the month. There's the walking group every Tuesday and every Thursday. So, I could do Tuesday, Thursday, Sunday.

DR: You could be gay 3 out of 7 days a week.

PS: Yes. And Saturday afternoon there’s sketching, so that’s four days out of the week. But it's also just people have gotten to know each other much more closely and, for me it's a very different experience, say, compared to the time I spent in Melbourne. I used to play gay tennis and I was part of East Group. And I did things like I was the education officer for the AIDS group. It was very much more formal, you know, we were doing things that were part of large grants from the government and I suppose the agenda seemed not very personal at all. But here you know everybody. There's such a level of intimacy isn't there really? Chris?

CW: Yeah there's a community. Whereas you know, Melbourne’s so huge there isn’t a community there are communities, but there's not acommunity. Here it's a community.

PS: I think you'd have to do something amazing not to find acceptance within the group.

CW: Everyone's lovely. Well, partly, it's because …

PS: You can’t afford not to be, you have to be …

CW: Or you’ll get abused. No, I think it's to do with sex. Largely the population here of gay people is elderly …

PS: Yes, we’re old.

CW: They're not hunting down tonight's delicious feast. So, there's …

PS: Yes, they are.

CW: So that causes a relaxed feeling …

PS: There's not the intensity ...

CW: No tension …

PS: There’s not the intensity of all those hormones working like mad.

CW No, it just doesn't work like that. It's about friendship.

DR: How many people would you say are involved?

PS: Oh, the last time they had one of those dos in the park, there would have been 70.

CW: Yeah, but Bendigo people came down too. I'd say there's 100 men in the vicinity who know about The Alluvians. They may only come to one thing or hardly anything but they know and they've got individual friends within that group or people who they’re close to.

David: Is it just men in the The Alluvians?

Phillip: It has been for many years. But there is certainly a policy to try and get women involved.

David: Do women go to the Botanical Garden walks?

Chris: Yeah, they go in an opposite direction, which is a sort of interesting thing. I have no idea how it happened. I don't think it suggests anything negative. It’s just a desire for the women not to be overwhelmed by the number of men, many of whom have dogs. Although the women have dogs as well. There's no animosity, just a respect, I think, for both groups. The men do respect and open everything up to women.

Phillip: And some of the Alluvians have walked with the lesbians in the opposite direction around the garden.

Chris: Yes, this is sensational!

Phillip: Amazing gesture.

Chris: But it was terrific, you know, they were saying – okay, we’re going to linkup. It's a bizarre situation because we all meet up at some point on the path anyway …

Phillip: And we share dogs a lot of time and dog information.

Chris: Dogs are actually a fairly significant link between people in an odd way.

Phillip: That's true. Because everyone's got the trauma of raising puppies.

DR: What's your story as a couple?

PS: Well, we are 1949 babies. We met in 1969 at Monash University. We were both doing Honours in English, and we had to do Old and Middle English. We were in the same class with Professor Steel, and we weren't enjoying it much to tell the truth.

CW: Oh, I thought you liked it.

PS: Well, I liked the poetry but I didn't like having to learn it as a language. Chris got his ashes and thorns all mixed up, and he asked me for help. And the sort of help that I gave was not really part of the curriculum.

CW: Phillip still has a very similar personality to the one he had in 1969 – a very outgoing, warm personality. I can't remember what I said, but I chose Philip to help me. I didn't think he was gay. I was barely coping with myself being gay at that stage.

DR: How old were you then?

CW: 18 or 19. I’d come out to myself in year 11, when I was 16 or 17. But I hadn't really come out widely to anybody. I got used to coming out all the time – at that stage anyone who was gay had to keep coming out. You know – mum, dad, the relatives, the brother and sister, the best friend – and everyone required a story, it was bloody hard work.

DR: Did you have a good story by that stage?

CW: I can’t remember what I said now.

PS: In the late 60s it was still completely criminal. We could have gone to jail. There was no acceptance for us.

CW: It was often best to come out to the girlfriends first. Just because the girlfriends were very accepting.

PS: Yeah, women tended to be much better about it.

CW: I came out to Gayle

PS: Who was my girlfriend at the time.

CW: Philip was presenting as straight, completely. And I took him as straight.

PS: I am straight. Ha, ha.

CW: I took him as a straight boy, just a really very nice straight boy. It didn't occur to me that he was gay. Anyway, I saw him in the Ming Wing, which is one of the buildings at Monash and I walked past him and he was deep kissing Gayle.

PS: Oh, I was not!

CW Extensive tongue kissing for like 10 minutes!

DR: Gayle or someone else?

CW: Yeah, it was Gayle.

PS: It was an experiment. But that was 1969 – it was the year of revolution.

CW: Yeah, there was a whole lot going on.

PS: And in our tutorial we had Kerry Langer, Albert Langer's wife.

CW: Albert Langer was a very famous name in the late 60s in terms of the moratoriums.

PS: And Monash was under siege really. They occupied the administration building for ages. The Vice Chancellor called a University-wide meeting to talk to everybody about what was going on. What the University's position was regarding police on campus – all those sorts of issues. But it was super political wasn’t it?

CW: Yeah, and being young, this was the big world that you suddenly discovered.

PS: Well, yeah, but we also walked into a sort of immense mess, didn't we really, in terms of our own struggle to find our own identity? It was against the backdrop of civil rights and everything else. It was just very hard to find your bearings.

CW: I can remember thinking that I was going to have a nervous breakdown. One of the reasons I joined the left was to help with the collection of money at Monash to support the Vietnamese National Liberation Front. I was happy to give money but I thought it might go to buy bullets, and I thought, I do not want to give money to kill somebody. I'm not that obsessed with the whole thing that I’d want to do that. This was such a tangle for me psychologically that I had to see one of the psychologists at Monash.

PS: Chris was part of the Labor Party, in a Young Labor group, weren’t you?

CW: I was. And extremely radical.

PS: And you and Gayle threw all those ...

CW: Things. We would have thrown some things. Metal barriers, I think …

PS: Into the pond.

PS: Everything was an issue. Car parking became an issue. The University set up barriers around various spots for staff car parking and that was regarded as just not proper. And so, Chris and Gayle and others disassembled these barriers and carried them over and threw them into the pond.

CW: There was a mock crucifixion at the same site which caused a huge national scandal. No one was really crucified.

PS: It was a time when it was very hard to concentrate on your work. It was an upheaval ’68, ’69, ‘70.

Then Chris completed his degree and decided to go out teaching and we were vaguely in contact with each other. We didn’t hook up. We just stayed in contact. I knew that he was very special, but I couldn't quite define it.

DR: Can you define it now?

PS: No, no. not really, It’s a mystery.

But we finished ... I got a Postgraduate Scholarship and stayed on to do my masters. Chris did his DipEd and went out teaching in Traralgon in the Latrobe Valley. Good old Traralgon. I stayed on in the English department tutoring and trying to finish my Masters which I wasn’t really very interested in. I went to America in August ’72 on a Ford Foundation Scholarship to write about Willa Cather – this woman in the early 20th century who was the literary discoverer of Nebraska, and a lesbian. She wrote novels about the prairie, about the opening up of the frontier in terms that weren’t about cowboys and Indians but more about what it was like to be a cultured and educated person marooned on the prairie in those days. She really was an amazing person. She dressed as a bloke – most of her early years as a Confederate soldier. So I thought she was interesting. Anyway, I got this scholarship, went over there, and when I came back, I had resolved not to muck around any longer but to find a husband and live a life, because it was just becoming ridiculous.

DR: So, was there a turning point for you that made that decision?

PS: I just realised I wasn’t that interested in academic life. And I wanted to have a much richer personal life than what I was having. I had to finish my Masters while I was in America and I‘d sort of delayed that – I was a shocking procrastinator, still am. But I thought, No, I’ve got to have a proper relationship, a serious relationship, that will be rewarding. So I came back, and my brother took me to a New Year’s Eve party. And there was Christopher wearing his little surfy kind of t-shirt, sitting across the room and I thought, That’s the one.

CW: I don’t know why.

PS: He was very, very cute and he had shoulder length thick, black hair and slate grey eyes. And he was very good looking.

CW: Really? You've never told me that before.

PS: No, you were very pretty, you were really attractive. Anyway, I invited him over. This lecturer in lit. at Rusden who we’d got to know said, Be careful of him, he’s a real radical and he may have an ASIO file.

CW: I think I might have.

PS: And I said boo-hoo to that and I found that he lived in Manningtree Road and we were living in Kinkora Road in Hawthorn, just a few streets away.

CW: Share houses. Mansions. It was a fantastic experience living in an old, dilapidated mansion.

PS: It was a typical student house-type experience.

DR: So did you pursue Chris?

PS: I did. I made myself known to the community at Manningtree Road. l called in with a bunch of flowers.

DR: Did you?

PS: Not really. You actually invited me down there for dinner or something. And I turned up and they all played this joke where they pretended that I had been expected to bring an eggbeater. They kept asking me where the eggbeater was. One of those stupid adolescent things. And I couldn't understand what they were on about. You didn't help very much, Chris.

CW: Yeah, I was a bit overwhelmed that someone should be …

PS: Pursuing you. And I was relentless in my pursuit.

CW: He was very determined, because I wasn't completely convinced that I wanted to settle down.

PS: Then in 1975 a bigger flat became available in Kinkora Road, and we moved in together and we've never really been apart since ’75. Is that right?

CW: Well, yeah, we were a couple in that … I had a mild fling in the middle of it.

PS: You don’t need to add that. I was just trying to plant a myth of complete monogamy.

CW: Well, I thought that we may as well come out.

… So this is my experience in parallel … so he's in America. I went down to Traralgon.

DR: A little bit of difference between Traralgon and New York.

CW: Absolutely.

PS: New York when I was there, was in absolute crisis. This was when the city was bankrupt. They had brownouts – the power system kept failing at night. Somebody had napalmed a whole lot of the animals in the zoo and you couldn't go to 42nd Street, but I was actually living in 42nd Street.

CW: [singing] Playing at the Y.M.C.A.

PS: I had six months living there, it was dreadful. I think it was the most barbaric experience I've ever had. I’ve never been in such physical danger.

CW: They only wanted to kiss you.

PS: They did not. I'm sure they wanted my money. When I arrived in New York the first time, the cab driver wanted me to sing hymns with him all the way from the airport to 42nd street. When we got there, I hadn't sung very well. Nor did I know how to tip properly and got that wrong. So he just threw my stuff all over 42nd street. He just emptied my bags on the road. So I was scurrying in and out of the traffic trying to find my underpants.

CW: He was 22.

PS: Yeah, that was ’72. I was going on 23 but I was still very childlike.

CW: You were way too young. Philip grew up in the outskirts of Melbourne in a rural setting. That was your world, wasn’t it?

PS: Yeah, I grew up in a semi-rural kind of life out near Berwick and my grandparents and parents had small farms. I’m intrinsically a Dandenong boy.

CW: And one of the reasons why we're here in Castlemaine is that Phillip loves the country.

PS: I’m only truly at home in the country, I think.

CW: Because that was his childhood, playing along the creek and so on.

PS: Yeah, I love the fact that our creek’s in flood because it reminds me of my childhood when the flooding of the creek every spring was just so exciting.

CW: So, right now we have to relentlessly go down and look at the creek.

Anyway, I arrived in Traralgon and I had a similar kind of very narrow, small life in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. So Monash was an eye-opener. An extraordinary thing for me. And I didn't know anyone. Nobody went to Monash from the school I went to, it was just me. I arrived in Taralgon by myself again and had to find a place to live and start this career and I couldn't easily find a place. In the main street, a Welsh woman suddenly opened her house to these young teachers. Everyone wanted to be in Melbourne largely, people didn't want to teach in the country. I met four young men in this woman's house. We all slept in two rooms, she was just making a lot of money. She had squashed all these men into her house – she was a single woman. We all decided that this was a horrible situation, and we weren't going to put up with it for much longer so we found a dilapidated farmhouse in the countryside.

PS: Very like a Leunig cartoon …

CW: We all moved in there.

PS: … goat on the roof. That sort of thing.

CW: There was a goat on the roof. My bedroom had a hole in the roof, so I could actually see the stars through it. It was a really rundown place, and these guys weren’t into the kind of excellent home-making that I was.

PS: They weren’t very neat or clean

CW: And by the spring a whole lot of new calves had been born and they nearly all had diarrhoea. And these guys would walk the poo through the house.

PS: Didn’t the calves come into the kitchen?

CW: Yes, there was one in the house – the doors didn't properly close. By that stage I was out. Not noisily, but out. I hadn't told my parents I was gay. But I was telling people I was really close to and managing that all right. There was a time when I didn't manage it and went to a psychologist in year 12. Anyway, I decided I’ll join the gay group down there. So, there was Latrobe Valley Gay Men and Lesbian Society. And I went to the first meeting and that involved a principal of a school no less, and a bloke who became a well-known gay activist in Melbourne.

PS: What Chris hasn’t told you is that of all those guys living in that house he was the only gay. He was the only gay in the village.

CW: I had to come out to them.

DR: Were they accepting?

CW: Yeah, they were. They were great. They were terrific. I mean, they didn't help me find a female partner or anything.

So anyway, to keep the story going. We're now in Kinkora Road. We were living on the ground floor of this huge old mansion for $26 a week.

CW: Alabaster light fittings. It was amazing. Terrific.

PS: Huge, beautiful ballroom.

CW: But rundown.

PS: Very rundown. Then we were all thrown out, because it got sold for the outrageous price of $90,000 – this massive thing! It recently got resold for about 15 million. We made another communal house with other couples. And that was a disaster. Didn't work, did it?

It was a great strain for us. I decided that I wasn't going to be an academic, that I'd go out and teach and discovered that I was perhaps the least talented teacher to ever hit the boards.

CW: At Scotch College.

PS: That was disastrous. I was so bad. So, I had to submit my Masters, do a DipEd and start work at Scotch. And I didn't know which way was up. I was just a mess.

CW: Yeah, you were stressed.

PS: So, we're very stressed and we're living in this house that we'd largely furnished. And it was difficult.

CW: It was an unhappy period because Phillip had all that going on. I was also obsessed because I was teaching in Sunshine.

PS: He’d left Traralgon.

CW: Sunshine was a challenge to me. I won’t go too far off the track but before I went to Sunshine, I had to go to the Education Department to ask if I could move out of Traralgon which I really liked in a lot of ways, because it was the country.

PS: And the country kids were rather sweet weren’t they?

CW: Yeah, there were a lot of good reasons to stay, but I knew I could not get a partner if I stayed in Traralgon because there weren't any gays in the village. So, the Education Department person gave me Sunshine and I went out there, found the school, and was shocked to see that there were lunch wrappings blowing around …

PS: On the ground.

CW: And I'd come from schools in the eastern suburbs where we didn't have lunch wrappings blowing around. I went to the office and I said to the woman I've been offered a place at this school, and I don't know whether to take it or not. Can I ask you a few questions? I can't really remember what they were, but they were just about how the school operated and so on. And at the end she said, Young man, my advice to you is don't come here.

PS: So, you were warned off going to Sunshine?

CW: Absolutely, and that's why I stayed there. I thought bugger it! I came back at the end of ’73, early ‘74.

PS: And that's when we went to this party. That’s where we met. That's where we properly hooked up.

I didn't know he was a vegetarian. So anyway, I was invited to dinner, I've had this strange meal with these friends of Christopher's who kept asking me where the eggbeater was. And then I invited him back and I thought right, I need to seduce this person but how to do it? I know. I'll cook him a really nice steak. And I presented him with an inch-thick fillet of beef.

CW: I can still see it on the plate. I managed it quite well. I can’t remember what I … did I eat the steak?

PS: You ate a little bit of it and then confessed to vegetarianism

CW: Yeah, okay, I'm glad I ate a little bit of it at least anyway.

PS: A little nibble around the edges.

CW: Bill, Phillip’s brother was there as well. So, it was just the three of us.

PS: However, I realised that I would need to clear away and I knew Chris was the sort of person who would help with clearing away. So, I raced down to the kitchen and there's a little alcove next to the stove. So I secreted myself in there and when he came down with the dishes, I leaped out.

CW: I knew that was some kind of sexual thing. Anyway, my life at Sunshine wasn't initially easy because well, I was young. I was very young looking and I was from the eastern suburbs.

DR: You would have been an easy target.

PS: He was neat but with flowing locks

CW: I was also a sort of yes person. If someone gave me some challenge, I’d say yes to taking it up. So when I started at the school I thought, The big challenge here is survival. How can I survive? So I jumped into it with great enthusiasm. The school, oddly, had recently received permission to run live radio broadcasts and they gave me the job of wiring up the school …

PS: Disaster.

CW: And here I am, you know, I’ve only been teaching for like two months. And I say yes, so they wouldn’t think it was a challenge. Well, it was a horrific challenge. Firstly, I had to climb up a two-story building. I found a really long ladder and I climbed up to the top of it, and then there was this sort of parapet and I had to pull myself up and over it.

PS: That’s outrageous!

CW: Anyway, I got up on the roof. And then fiddled with the wiring and whatever. And it was lunchtime, and the kids could see me, and they started yelling stuff at me and then they got into a chorus and the chorus was, Mr. Wheat’s a fairy, Mr Wheat’s a fairy. I was glad they continued to use the ‘Mr.’

PS: Oh no!

CW: I was standing on the roof and thinking, Shit, this is not good. Anyway, that only reinforced my decision to stay on, rather than leave the school.

PS: I can imagine, in your case, that would make you so much more determined.

CW: Yeah. I ended up staying at the school for over 40 years.

DR: Were you out at the school?

CW: I was out to all the staff. I decided the whole staff should know …

PS: But not initially, it happened a bit later on, didn't it?

CW: It happened pretty soon. I remember arriving in the school and saying to myself, come out to the staff, because that was the time gay liberation was just starting and I was not really active in the movement, but I was completely on the side of it. So I came out to them. Not to any of the kids. I didn't come out to the kids for decades because I realised, particularly in a school like that, where there are kids who can't read properly and I was very active in the literacy program, that they're not going to want to sit in a room with a teacher who's gay because it was way too early in the whole thing. So I didn't come out to the kids. There were brave young gay teachers who were coming out to kids, but I didn't. So then I settled down in the school basically and all was fine.

PS: Whereas, I didn’t have any challenges with coming out at work. Because the sheltered environment of the English department was hardly any problem at all. There was one fellow tutor who said, I heard that you told people you're a homosexual. I said, Yeah, of course. I am a gay person. He could not believe it, he was absolutely staggered. He said, You know it’s illegal?’ I said, Yes, I know that but there's quite a few things that are illegal. But his surprise and aghastness was sensational from my point of view. I thought it was just so silly, because everyone knew, and it wasn't a big deal. But the parents represented the great difficulty in my life.

DR: Your parents?

PS: Yes, they were extraordinarily difficult to come out to. I tried allsorts of things. Eventually I thought, Well, I really have to tell them properly and formally. I want them to know, because it’s all innuendo and nothing said explicitly. So, I wrote it down. I wrote that I didn’t feel they had anything to worry about, that I’d found true happiness and Freud was way out of date, and it was nothing to do with absent fathers and controlling mothers but just an inescapable truth of the person. I wrote it down and quite a few weeks went by, and I heard nothing. Eventually, they were living in Flinders, and I was invited down for dinner. It was winter, and I was very cold, and the fire was going, and we had the meal and I said, Did you get my letter? And Mum said, What letter? And Dad said, I burned it. And that was my coming out.

DR: Oh, my goodness! Your mum never saw the letter?

PS: No, I don’t think she ever got the chance to read it. But they were just completely passive, and completely unaccepting. It was it was a horror for them.

DR: Did they meet Chris?

PS: Yes, they wouldn't speak to him, but they met. Well, they did speak to you. Dad was kind of quite nice to you.

CW: I did feel a kind of coldness.

PS: You didn’t feel hostility?

CW: No, no, I didn’t.

PS: But they hardly communicated with you did they?

CW: Yeah, but that was their way of coping. I think they were being polite to me and to you. And the only way they could do it was just to pretend that you never sent a letter. Whatever. Although we were living in the same house.

DR: Was this the 70s as well?

CW: Yeah, still the 70s.

DR: Did you sense then that you were going to stay together as a couple? Was that understood between you?

CW: Yeah, I think so. It was a serious relationship.

PS: In those years in the 70s and into the 80s, there was always a possibility that our relationship would fracture under the pressures that we were experiencing. Due to being gay. I just felt that it couldn't last, that we faced so many problems really. And we couldn't agree on a lot of things.

CW: Oh, did we argue about certain things?

PS: Well, Chris wasn't happy about the house. I went out and bought that house in Surry Hills.

CW: Oh, Yeah. Because I was romantic. I think I had these visions ...

PS: Of a very groovy urban life.

CW: That sort of thing. And Philip took a risk and at quite a young age started buying a house and paying it off. And I didn't want to live in the eastern suburbs because I'd grown up in the eastern suburbs. And I just wanted the excitement of Hawthorn really.

PS: The madness of it. You did get to live in Richmond eventually.

CW: Finally. I was not particularly supportive but Phillip just pushed ahead.

PS: I just thought I can't go along with this because I tried to buy a house in Hawthorn and that shot overnight to some astronomical price. So, I went out and bought a house in Surry Hills, which was then a rundown little State government-funded suburb of the 1920s and 30s, full of weatherboards collapsing but on big blocks. And I thought, it's surrounded by Canterbury, Kew, Balwyn, it's going to go up in price. And indeed it did. It went up by gazillions, didn't it? So, it proved to be a really good investment. But Chris had lived in the outer eastern suburbs. For him it was full of trauma really, it was full of claustrophobia, wasn’t it? You felt trapped living there?

CW: I felt somehow or other that the inner-city was exciting. Yeah, and I wanted to go there. So, I didn't block Phillip, but I wasn't particularly supportive. For me, it was, Oh god! But eventually I settled down quite happily.

PS: You loved living there eventually

CW: Yeah, eventually I was happy. So, it took a little while for me to cheer up. The other thing is that I was driving from Surry Hills to Sunshine and that was a bit of a hike.

PS: There was an underlying tension about whether we could survive our jobs.

CW: Yeah, both of us were stressed.

PS: I abandoned Scotch College, went back to Monash and got a job in the administration of the Arts Faculty and worked there for decades. And even though I think I was totally secure, I didn't feel it. I felt under a huge range of different pressures. I'd moved out of the English department into another world entirely.

DR: Did you ever consider getting married?

PS: Getting married? Yes, it's still on the agenda.

CW: Phillip would like to

PS: It became more pressing when I got ill.

CW: There wasn’t a lot of talk of marriage until …

PS: There was no possibility. Nobody could imagine gay marriage when we were younger.

CW: Yes, you see it was illegal. The gay marriage thing is really only about 15 years old or something. Prior to that, just coming out was a big deal. It was regarded as quite a radical step. A tiny little thing for me is that I was somewhat active in the gay liberation movement in Melbourne. At one stage gay teachers were asked, would they mind revealing themselves and standing on street corners. This sounds crazy – standing on street corners in Melbourne! Somehow I must have volunteered to stand on the street corner – it was Swanston and Collins – with a sign saying ‘I'm a gay teacher’.

DR: You’re joking, is there a photo of that?

CR: I swear, no one ever photographed me. I remember standing there alone. No one said offensive things and I think I could only hack it for about 40 minutes or something.

There was no negative stuff. So, the marriage thing didn't really come up until, well, when it came up – your memory is better than mine. And I didn't want to because it seemed to me to be stupid to mimic heterosexuals when heterosexuals were constantly showing us that marriage didn't work very well. And so, I just said to Phil, no, I don’t want to wear a ring saying I'm married to someone when it’s what a heterosexual would do. Now with Philip continuing to be sick, he wants to marry. I’m happy to, but I feel it's really hard to actually organise a serious marriage because you've got to … who do you not invite and who do you invite? I think that we would have to invite a huge number of people without hurting feelings. So, I find that quite a difficult thing. To me, the fact that our relationship is well over 40 years and will probably be into 50 years. That's enough to prove the strength of our relationship.

PS: In fact, if we had been able to get married back in the 70s or 80s, it would have made a huge difference to our sense of security, I think.

CW: We would have been more secure you mean?

PS: Yeah, I think so. But it wasn't ever a possibility. I mean, we weren't legal then, we were barely legal.

DR: What did that feel like, being illegal?

PS: It felt dreadful.

CW: But we just grew up with it, there was nothing else, you know.

PS: Yeah. There was a weird thing, a whole world of not being out, a whole repressed world. So many incredibly camp characters on the ABC who would never acknowledge themselves as homosexual.

CW: They were just ‘really happy’.

PS: Just very ‘cheerful’. So once you were out, you were confined to all the stereotypes that society could throw at you. There was also a kind of underground freedom, but I had one friend who was apprehended and forced to undergo weekly psychiatric counselling – this was when I was in Year 12 doing matriculation. He had to report to the police station each week. He had to attend a psychiatrist who used electro-convulsive therapy on him to get him attracted to … you know, he had to look at photographs. He was forced to undergo conversion therapy. His mother drove him to all the sessions. I had him as a living example right next to me – my best friend, who enjoyed literature and art like I did, and we were together on a lot of things. He had a criminal record as well, just to add to it all. Dreadful, really dreadful. There were all sorts of joys because you were young and you had a lot of energy and you felt fantastic and the world was incredibly, unbearably sexy, but at the same time, there was fear running throughout the whole thing.

DR: Did you ever experience any harassment or homophobia?

CW: I didn't actually, and I'm surprised to be able to say that. I think sometimes you realised in the early days that people were slightly tense about you, but they didn't express anything negative.

PS: No, I didn't experience anything very direct.

CW: But we lived in a world which was similar to our own middle class, polite world. And women were accepting of gay men quite early. Certainly, the women we knew were all quite warm towards us and they knew we were gay.

PS: The most intense homophobia I've experienced was a family matter.

CW: My brother was wonderful. I came out to him very early on. He said he didn't mind, instantly.

PS: He was remarkably mature and spoke to both of us. And I had the support of my other brother. But Bill simply wasn't able to ever express anything really. Mum and dad would never have coped with the idea that they had given rise to two homosexuals ...

DR: But they knew?

PS: They did know. They knew but they didn’t like it.

CW: When I came out to mine, they said ‘we know’.

DR: And how do you feel here in Castlemaine?

PS: I feel totally safe here.

CW Yeah, it's a lovely community.

PS: We've not met with the slightest negativity anywhere.

CW: I don't think so.

PS: We're very fortunate. Even you know some of our older more conservative neighbours, they’re still completely open and friendly, they just acknowledge us as a couple. They are good.

DR: Can you talk about ‘Queer’ and how that's been adopted by the younger generation?

PS: There's a friend of ours, she's a doctor, and she doesn't like the term ‘queer’ because for her generation, it's pejorative. It's got a negative connotation – you are perverse, you are queer, you're not mainstream, you're not straight. And she prefers to be known as a gay woman, not as queer. But I suppose in so many ways, people are looking for a broader definition of life really, and gay is more confining. I sort of share her point of view, I don't quite like queer I don't want to be known as odd or eccentric in some sort of weird way. That's what that term says for me. I’d prefer to be a gay person.

CW: A few weeks ago, I got on a train. It was an advertising train – you know how they take a whole carriage as an advertisement? And it had the word ‘QUEER’ – in letters this high, just ‘QUEER’. I thought it was wonderful, a wonderful moment. I almost laughed out loud. I think of the idea of this, compared to say 10 years ago, when it wouldn't have happened. It was a queer carriage full of straight people who didn’t care what carriage they were travelling in.

DR: Yeah, it was a great exhibition

CW: Yeah, it was. Now, would you like some soup and stay for lunch?

PS: We’re not really local. We're local insofar as we've been here for 20, 22 years – most of that time we had a holiday house because we were living in St Kilda. But we don't regret moving here full time. It's been wonderful.

We did it because I wasn't very well. I got various forms of cancer, one after the other and I’m still on chemo and stuff for a thing called multiple myeloma. So, I couldn’t cope with our St Kilda place. It has massive numbers of steps to get up, so everything's nice and level here. But that wasn’t the sole reason, it was also to retire. Chris had finally left school. He got his certificate for 45 years’ service and then stayed on for another five.

We originally bought this place in 2000 but we didn’t move here until 2018.

DR: Did you know about the gay community here or have friends within that community when you had the holiday house?

PS: Kind of. Well, there’s a sort of Central Highlands set up really. Before this we had a property at Smeaton, and we had some lesbian friends who were very much involved in establishing the Pride Parade and the Chillout Festival. And there were Castlemaine people who came to that and it's all one. Even a little town like Smeaton had quite a gay contingent, didn’t it?

CW: Yeah. And there are connections between Kyneton, Daylesford, Trentham, Newstead, Castlemaine – and people know gay people in each of the towns. Not necessarily well, but there's kind of links that go on.

PS: It really started with Jack's cafe restaurant in Daylesford. We're talking about late 70s, 80s. There was the Harvest Cafe, which wasn't gay, but everyone was completely stoned.

DR: Including you?

P&C: Not really, no. We were more into …

CW: I took drugs when I was in my very early 20s …

PS: Tut tut tut, but mainly we're into high fibre rather than drugs now. So, we all started getting to Jack's Cafe, which was the genesis of the gay world, really, in Daylesford, wasn’t it?

PS: Friday nights at Jack's was extremely funny. There were competitions and that just naturally evolved into Chillout with …

CW: Thousands!

PS: … gumboot throwing and rural pursuits.

CW: Chillout, it's a big thing now.

PS: Huge.

DR: Did you go to that regularly?

PS: Oh, yeah, we went quite a few times.

CW: I was so overworked. I can remember being there – we parked and I sat in the car and corrected year 12 essays.

DR: How has the gay scene or queer scene changed over the last 20 years or so since you've been coming here?

PS: It's evolved massively compared to when we first came here.

CW: Yeah, it has, thanks to The Alluvians really ...

PS: That focused it.

CW: Yeah. You look at the site now and there's things going on the whole year ...

PS: There’s almost too much to go to. There’re games nights and there's car things which I am not that interested in. But there's art things, there’s the sketching group – there’s loads. But also every Sunday they now get together at the Morocco bar, in town, that's on every last Sunday of the month. There's the walking group every Tuesday and every Thursday. So, I could do Tuesday, Thursday, Sunday.

DR: You could be gay 3 out of 7 days a week.

PS: Yes. And Saturday afternoon there’s sketching, so that’s four days out of the week. But it's also just people have gotten to know each other much more closely and, for me it's a very different experience, say, compared to the time I spent in Melbourne. I used to play gay tennis and I was part of East Group. And I did things like I was the education officer for the AIDS group. It was very much more formal, you know, we were doing things that were part of large grants from the government and I suppose the agenda seemed not very personal at all. But here you know everybody. There's such a level of intimacy isn't there really? Chris?

CW: Yeah there's a community. Whereas you know, Melbourne’s so huge there isn’t a community there are communities, but there's not acommunity. Here it's a community.

PS: I think you'd have to do something amazing not to find acceptance within the group.

CW: Everyone's lovely. Well, partly, it's because …

PS: You can’t afford not to be, you have to be …

CW: Or you’ll get abused. No, I think it's to do with sex. Largely the population here of gay people is elderly …

PS: Yes, we’re old.

CW: They're not hunting down tonight's delicious feast. So, there's …

PS: Yes, they are.

CW: So that causes a relaxed feeling …

PS: There's not the intensity ...

CW: No tension …

PS: There’s not the intensity of all those hormones working like mad.

CW No, it just doesn't work like that. It's about friendship.

DR: How many people would you say are involved?

PS: Oh, the last time they had one of those dos in the park, there would have been 70.

CW: Yeah, but Bendigo people came down too. I'd say there's 100 men in the vicinity who know about The Alluvians. They may only come to one thing or hardly anything but they know and they've got individual friends within that group or people who they’re close to.

David: Is it just men in the The Alluvians?

Phillip: It has been for many years. But there is certainly a policy to try and get women involved.

David: Do women go to the Botanical Garden walks?

Chris: Yeah, they go in an opposite direction, which is a sort of interesting thing. I have no idea how it happened. I don't think it suggests anything negative. It’s just a desire for the women not to be overwhelmed by the number of men, many of whom have dogs. Although the women have dogs as well. There's no animosity, just a respect, I think, for both groups. The men do respect and open everything up to women.

Phillip: And some of the Alluvians have walked with the lesbians in the opposite direction around the garden.

Chris: Yes, this is sensational!

Phillip: Amazing gesture.

Chris: But it was terrific, you know, they were saying – okay, we’re going to linkup. It's a bizarre situation because we all meet up at some point on the path anyway …

Phillip: And we share dogs a lot of time and dog information.

Chris: Dogs are actually a fairly significant link between people in an odd way.

Phillip: That's true. Because everyone's got the trauma of raising puppies.

DR: What's your story as a couple?

PS: Well, we are 1949 babies. We met in 1969 at Monash University. We were both doing Honours in English, and we had to do Old and Middle English. We were in the same class with Professor Steel, and we weren't enjoying it much to tell the truth.

CW: Oh, I thought you liked it.

PS: Well, I liked the poetry but I didn't like having to learn it as a language. Chris got his ashes and thorns all mixed up, and he asked me for help. And the sort of help that I gave was not really part of the curriculum.

CW: Phillip still has a very similar personality to the one he had in 1969 – a very outgoing, warm personality. I can't remember what I said, but I chose Philip to help me. I didn't think he was gay. I was barely coping with myself being gay at that stage.

DR: How old were you then?

CW: 18 or 19. I’d come out to myself in year 11, when I was 16 or 17. But I hadn't really come out widely to anybody. I got used to coming out all the time – at that stage anyone who was gay had to keep coming out. You know – mum, dad, the relatives, the brother and sister, the best friend – and everyone required a story, it was bloody hard work.

DR: Did you have a good story by that stage?

CW: I can’t remember what I said now.

PS: In the late 60s it was still completely criminal. We could have gone to jail. There was no acceptance for us.

CW: It was often best to come out to the girlfriends first. Just because the girlfriends were very accepting.

PS: Yeah, women tended to be much better about it.

CW: I came out to Gayle

PS: Who was my girlfriend at the time.

CW: Philip was presenting as straight, completely. And I took him as straight.

PS: I am straight. Ha, ha.

CW: I took him as a straight boy, just a really very nice straight boy. It didn't occur to me that he was gay. Anyway, I saw him in the Ming Wing, which is one of the buildings at Monash and I walked past him and he was deep kissing Gayle.

PS: Oh, I was not!

CW Extensive tongue kissing for like 10 minutes!

DR: Gayle or someone else?

CW: Yeah, it was Gayle.

PS: It was an experiment. But that was 1969 – it was the year of revolution.

CW: Yeah, there was a whole lot going on.

PS: And in our tutorial we had Kerry Langer, Albert Langer's wife.

CW: Albert Langer was a very famous name in the late 60s in terms of the moratoriums.

PS: And Monash was under siege really. They occupied the administration building for ages. The Vice Chancellor called a University-wide meeting to talk to everybody about what was going on. What the University's position was regarding police on campus – all those sorts of issues. But it was super political wasn’t it?

CW: Yeah, and being young, this was the big world that you suddenly discovered.

PS: Well, yeah, but we also walked into a sort of immense mess, didn't we really, in terms of our own struggle to find our own identity? It was against the backdrop of civil rights and everything else. It was just very hard to find your bearings.

CW: I can remember thinking that I was going to have a nervous breakdown. One of the reasons I joined the left was to help with the collection of money at Monash to support the Vietnamese National Liberation Front. I was happy to give money but I thought it might go to buy bullets, and I thought, I do not want to give money to kill somebody. I'm not that obsessed with the whole thing that I’d want to do that. This was such a tangle for me psychologically that I had to see one of the psychologists at Monash.

PS: Chris was part of the Labor Party, in a Young Labor group, weren’t you?

CW: I was. And extremely radical.

PS: And you and Gayle threw all those ...

CW: Things. We would have thrown some things. Metal barriers, I think …

PS: Into the pond.

PS: Everything was an issue. Car parking became an issue. The University set up barriers around various spots for staff car parking and that was regarded as just not proper. And so, Chris and Gayle and others disassembled these barriers and carried them over and threw them into the pond.

CW: There was a mock crucifixion at the same site which caused a huge national scandal. No one was really crucified.

PS: It was a time when it was very hard to concentrate on your work. It was an upheaval ’68, ’69, ‘70.

Then Chris completed his degree and decided to go out teaching and we were vaguely in contact with each other. We didn’t hook up. We just stayed in contact. I knew that he was very special, but I couldn't quite define it.

DR: Can you define it now?

PS: No, no. not really, It’s a mystery.

But we finished ... I got a Postgraduate Scholarship and stayed on to do my masters. Chris did his DipEd and went out teaching in Traralgon in the Latrobe Valley. Good old Traralgon. I stayed on in the English department tutoring and trying to finish my Masters which I wasn’t really very interested in. I went to America in August ’72 on a Ford Foundation Scholarship to write about Willa Cather – this woman in the early 20th century who was the literary discoverer of Nebraska, and a lesbian. She wrote novels about the prairie, about the opening up of the frontier in terms that weren’t about cowboys and Indians but more about what it was like to be a cultured and educated person marooned on the prairie in those days. She really was an amazing person. She dressed as a bloke – most of her early years as a Confederate soldier. So I thought she was interesting. Anyway, I got this scholarship, went over there, and when I came back, I had resolved not to muck around any longer but to find a husband and live a life, because it was just becoming ridiculous.

DR: So, was there a turning point for you that made that decision?

PS: I just realised I wasn’t that interested in academic life. And I wanted to have a much richer personal life than what I was having. I had to finish my Masters while I was in America and I‘d sort of delayed that – I was a shocking procrastinator, still am. But I thought, No, I’ve got to have a proper relationship, a serious relationship, that will be rewarding. So I came back, and my brother took me to a New Year’s Eve party. And there was Christopher wearing his little surfy kind of t-shirt, sitting across the room and I thought, That’s the one.

CW: I don’t know why.

PS: He was very, very cute and he had shoulder length thick, black hair and slate grey eyes. And he was very good looking.

CW: Really? You've never told me that before.

PS: No, you were very pretty, you were really attractive. Anyway, I invited him over. This lecturer in lit. at Rusden who we’d got to know said, Be careful of him, he’s a real radical and he may have an ASIO file.

CW: I think I might have.

PS: And I said boo-hoo to that and I found that he lived in Manningtree Road and we were living in Kinkora Road in Hawthorn, just a few streets away.

CW: Share houses. Mansions. It was a fantastic experience living in an old, dilapidated mansion.

PS: It was a typical student house-type experience.

DR: So did you pursue Chris?

PS: I did. I made myself known to the community at Manningtree Road. l called in with a bunch of flowers.

DR: Did you?

PS: Not really. You actually invited me down there for dinner or something. And I turned up and they all played this joke where they pretended that I had been expected to bring an eggbeater. They kept asking me where the eggbeater was. One of those stupid adolescent things. And I couldn't understand what they were on about. You didn't help very much, Chris.

CW: Yeah, I was a bit overwhelmed that someone should be …

PS: Pursuing you. And I was relentless in my pursuit.

CW: He was very determined, because I wasn't completely convinced that I wanted to settle down.

PS: Then in 1975 a bigger flat became available in Kinkora Road, and we moved in together and we've never really been apart since ’75. Is that right?

CW: Well, yeah, we were a couple in that … I had a mild fling in the middle of it.

PS: You don’t need to add that. I was just trying to plant a myth of complete monogamy.

CW: Well, I thought that we may as well come out.

… So this is my experience in parallel … so he's in America. I went down to Traralgon.

DR: A little bit of difference between Traralgon and New York.

CW: Absolutely.

PS: New York when I was there, was in absolute crisis. This was when the city was bankrupt. They had brownouts – the power system kept failing at night. Somebody had napalmed a whole lot of the animals in the zoo and you couldn't go to 42nd Street, but I was actually living in 42nd Street.

CW: [singing] Playing at the Y.M.C.A.

PS: I had six months living there, it was dreadful. I think it was the most barbaric experience I've ever had. I’ve never been in such physical danger.

CW: They only wanted to kiss you.

PS: They did not. I'm sure they wanted my money. When I arrived in New York the first time, the cab driver wanted me to sing hymns with him all the way from the airport to 42nd street. When we got there, I hadn't sung very well. Nor did I know how to tip properly and got that wrong. So he just threw my stuff all over 42nd street. He just emptied my bags on the road. So I was scurrying in and out of the traffic trying to find my underpants.

CW: He was 22.

PS: Yeah, that was ’72. I was going on 23 but I was still very childlike.

CW: You were way too young. Philip grew up in the outskirts of Melbourne in a rural setting. That was your world, wasn’t it?

PS: Yeah, I grew up in a semi-rural kind of life out near Berwick and my grandparents and parents had small farms. I’m intrinsically a Dandenong boy.

CW: And one of the reasons why we're here in Castlemaine is that Phillip loves the country.

PS: I’m only truly at home in the country, I think.

CW: Because that was his childhood, playing along the creek and so on.

PS: Yeah, I love the fact that our creek’s in flood because it reminds me of my childhood when the flooding of the creek every spring was just so exciting.

CW: So, right now we have to relentlessly go down and look at the creek.

Anyway, I arrived in Traralgon and I had a similar kind of very narrow, small life in the eastern suburbs of Melbourne. So Monash was an eye-opener. An extraordinary thing for me. And I didn't know anyone. Nobody went to Monash from the school I went to, it was just me. I arrived in Taralgon by myself again and had to find a place to live and start this career and I couldn't easily find a place. In the main street, a Welsh woman suddenly opened her house to these young teachers. Everyone wanted to be in Melbourne largely, people didn't want to teach in the country. I met four young men in this woman's house. We all slept in two rooms, she was just making a lot of money. She had squashed all these men into her house – she was a single woman. We all decided that this was a horrible situation, and we weren't going to put up with it for much longer so we found a dilapidated farmhouse in the countryside.

PS: Very like a Leunig cartoon …

CW: We all moved in there.

PS: … goat on the roof. That sort of thing.

CW: There was a goat on the roof. My bedroom had a hole in the roof, so I could actually see the stars through it. It was a really rundown place, and these guys weren’t into the kind of excellent home-making that I was.

PS: They weren’t very neat or clean

CW: And by the spring a whole lot of new calves had been born and they nearly all had diarrhoea. And these guys would walk the poo through the house.

PS: Didn’t the calves come into the kitchen?

CW: Yes, there was one in the house – the doors didn't properly close. By that stage I was out. Not noisily, but out. I hadn't told my parents I was gay. But I was telling people I was really close to and managing that all right. There was a time when I didn't manage it and went to a psychologist in year 12. Anyway, I decided I’ll join the gay group down there. So, there was Latrobe Valley Gay Men and Lesbian Society. And I went to the first meeting and that involved a principal of a school no less, and a bloke who became a well-known gay activist in Melbourne.

PS: What Chris hasn’t told you is that of all those guys living in that house he was the only gay. He was the only gay in the village.

CW: I had to come out to them.

DR: Were they accepting?

CW: Yeah, they were. They were great. They were terrific. I mean, they didn't help me find a female partner or anything.

So anyway, to keep the story going. We're now in Kinkora Road. We were living on the ground floor of this huge old mansion for $26 a week.

CW: Alabaster light fittings. It was amazing. Terrific.

PS: Huge, beautiful ballroom.

CW: But rundown.

PS: Very rundown. Then we were all thrown out, because it got sold for the outrageous price of $90,000 – this massive thing! It recently got resold for about 15 million. We made another communal house with other couples. And that was a disaster. Didn't work, did it?

It was a great strain for us. I decided that I wasn't going to be an academic, that I'd go out and teach and discovered that I was perhaps the least talented teacher to ever hit the boards.

CW: At Scotch College.

PS: That was disastrous. I was so bad. So, I had to submit my Masters, do a DipEd and start work at Scotch. And I didn't know which way was up. I was just a mess.

CW: Yeah, you were stressed.

PS: So, we're very stressed and we're living in this house that we'd largely furnished. And it was difficult.

CW: It was an unhappy period because Phillip had all that going on. I was also obsessed because I was teaching in Sunshine.

PS: He’d left Traralgon.

CW: Sunshine was a challenge to me. I won’t go too far off the track but before I went to Sunshine, I had to go to the Education Department to ask if I could move out of Traralgon which I really liked in a lot of ways, because it was the country.

PS: And the country kids were rather sweet weren’t they?

CW: Yeah, there were a lot of good reasons to stay, but I knew I could not get a partner if I stayed in Traralgon because there weren't any gays in the village. So, the Education Department person gave me Sunshine and I went out there, found the school, and was shocked to see that there were lunch wrappings blowing around …

PS: On the ground.

CW: And I'd come from schools in the eastern suburbs where we didn't have lunch wrappings blowing around. I went to the office and I said to the woman I've been offered a place at this school, and I don't know whether to take it or not. Can I ask you a few questions? I can't really remember what they were, but they were just about how the school operated and so on. And at the end she said, Young man, my advice to you is don't come here.

PS: So, you were warned off going to Sunshine?

CW: Absolutely, and that's why I stayed there. I thought bugger it! I came back at the end of ’73, early ‘74.

PS: And that's when we went to this party. That’s where we met. That's where we properly hooked up.

I didn't know he was a vegetarian. So anyway, I was invited to dinner, I've had this strange meal with these friends of Christopher's who kept asking me where the eggbeater was. And then I invited him back and I thought right, I need to seduce this person but how to do it? I know. I'll cook him a really nice steak. And I presented him with an inch-thick fillet of beef.

CW: I can still see it on the plate. I managed it quite well. I can’t remember what I … did I eat the steak?

PS: You ate a little bit of it and then confessed to vegetarianism

CW: Yeah, okay, I'm glad I ate a little bit of it at least anyway.

PS: A little nibble around the edges.

CW: Bill, Phillip’s brother was there as well. So, it was just the three of us.

PS: However, I realised that I would need to clear away and I knew Chris was the sort of person who would help with clearing away. So, I raced down to the kitchen and there's a little alcove next to the stove. So I secreted myself in there and when he came down with the dishes, I leaped out.

CW: I knew that was some kind of sexual thing. Anyway, my life at Sunshine wasn't initially easy because well, I was young. I was very young looking and I was from the eastern suburbs.

DR: You would have been an easy target.

PS: He was neat but with flowing locks

CW: I was also a sort of yes person. If someone gave me some challenge, I’d say yes to taking it up. So when I started at the school I thought, The big challenge here is survival. How can I survive? So I jumped into it with great enthusiasm. The school, oddly, had recently received permission to run live radio broadcasts and they gave me the job of wiring up the school …

PS: Disaster.

CW: And here I am, you know, I’ve only been teaching for like two months. And I say yes, so they wouldn’t think it was a challenge. Well, it was a horrific challenge. Firstly, I had to climb up a two-story building. I found a really long ladder and I climbed up to the top of it, and then there was this sort of parapet and I had to pull myself up and over it.

PS: That’s outrageous!

CW: Anyway, I got up on the roof. And then fiddled with the wiring and whatever. And it was lunchtime, and the kids could see me, and they started yelling stuff at me and then they got into a chorus and the chorus was, Mr. Wheat’s a fairy, Mr Wheat’s a fairy. I was glad they continued to use the ‘Mr.’

PS: Oh no!

CW: I was standing on the roof and thinking, Shit, this is not good. Anyway, that only reinforced my decision to stay on, rather than leave the school.

PS: I can imagine, in your case, that would make you so much more determined.

CW: Yeah. I ended up staying at the school for over 40 years.

DR: Were you out at the school?

CW: I was out to all the staff. I decided the whole staff should know …

PS: But not initially, it happened a bit later on, didn't it?

CW: It happened pretty soon. I remember arriving in the school and saying to myself, come out to the staff, because that was the time gay liberation was just starting and I was not really active in the movement, but I was completely on the side of it. So I came out to them. Not to any of the kids. I didn't come out to the kids for decades because I realised, particularly in a school like that, where there are kids who can't read properly and I was very active in the literacy program, that they're not going to want to sit in a room with a teacher who's gay because it was way too early in the whole thing. So I didn't come out to the kids. There were brave young gay teachers who were coming out to kids, but I didn't. So then I settled down in the school basically and all was fine.

PS: Whereas, I didn’t have any challenges with coming out at work. Because the sheltered environment of the English department was hardly any problem at all. There was one fellow tutor who said, I heard that you told people you're a homosexual. I said, Yeah, of course. I am a gay person. He could not believe it, he was absolutely staggered. He said, You know it’s illegal?’ I said, Yes, I know that but there's quite a few things that are illegal. But his surprise and aghastness was sensational from my point of view. I thought it was just so silly, because everyone knew, and it wasn't a big deal. But the parents represented the great difficulty in my life.

DR: Your parents?

PS: Yes, they were extraordinarily difficult to come out to. I tried allsorts of things. Eventually I thought, Well, I really have to tell them properly and formally. I want them to know, because it’s all innuendo and nothing said explicitly. So, I wrote it down. I wrote that I didn’t feel they had anything to worry about, that I’d found true happiness and Freud was way out of date, and it was nothing to do with absent fathers and controlling mothers but just an inescapable truth of the person. I wrote it down and quite a few weeks went by, and I heard nothing. Eventually, they were living in Flinders, and I was invited down for dinner. It was winter, and I was very cold, and the fire was going, and we had the meal and I said, Did you get my letter? And Mum said, What letter? And Dad said, I burned it. And that was my coming out.

DR: Oh, my goodness! Your mum never saw the letter?

PS: No, I don’t think she ever got the chance to read it. But they were just completely passive, and completely unaccepting. It was it was a horror for them.

DR: Did they meet Chris?

PS: Yes, they wouldn't speak to him, but they met. Well, they did speak to you. Dad was kind of quite nice to you.

CW: I did feel a kind of coldness.

PS: You didn’t feel hostility?

CW: No, no, I didn’t.

PS: But they hardly communicated with you did they?

CW: Yeah, but that was their way of coping. I think they were being polite to me and to you. And the only way they could do it was just to pretend that you never sent a letter. Whatever. Although we were living in the same house.

DR: Was this the 70s as well?

CW: Yeah, still the 70s.

DR: Did you sense then that you were going to stay together as a couple? Was that understood between you?

CW: Yeah, I think so. It was a serious relationship.

PS: In those years in the 70s and into the 80s, there was always a possibility that our relationship would fracture under the pressures that we were experiencing. Due to being gay. I just felt that it couldn't last, that we faced so many problems really. And we couldn't agree on a lot of things.

CW: Oh, did we argue about certain things?

PS: Well, Chris wasn't happy about the house. I went out and bought that house in Surry Hills.

CW: Oh, Yeah. Because I was romantic. I think I had these visions ...

PS: Of a very groovy urban life.

CW: That sort of thing. And Philip took a risk and at quite a young age started buying a house and paying it off. And I didn't want to live in the eastern suburbs because I'd grown up in the eastern suburbs. And I just wanted the excitement of Hawthorn really.

PS: The madness of it. You did get to live in Richmond eventually.

CW: Finally. I was not particularly supportive but Phillip just pushed ahead.

PS: I just thought I can't go along with this because I tried to buy a house in Hawthorn and that shot overnight to some astronomical price. So, I went out and bought a house in Surry Hills, which was then a rundown little State government-funded suburb of the 1920s and 30s, full of weatherboards collapsing but on big blocks. And I thought, it's surrounded by Canterbury, Kew, Balwyn, it's going to go up in price. And indeed it did. It went up by gazillions, didn't it? So, it proved to be a really good investment. But Chris had lived in the outer eastern suburbs. For him it was full of trauma really, it was full of claustrophobia, wasn’t it? You felt trapped living there?

CW: I felt somehow or other that the inner-city was exciting. Yeah, and I wanted to go there. So, I didn't block Phillip, but I wasn't particularly supportive. For me, it was, Oh god! But eventually I settled down quite happily.

PS: You loved living there eventually

CW: Yeah, eventually I was happy. So, it took a little while for me to cheer up. The other thing is that I was driving from Surry Hills to Sunshine and that was a bit of a hike.

PS: There was an underlying tension about whether we could survive our jobs.

CW: Yeah, both of us were stressed.

PS: I abandoned Scotch College, went back to Monash and got a job in the administration of the Arts Faculty and worked there for decades. And even though I think I was totally secure, I didn't feel it. I felt under a huge range of different pressures. I'd moved out of the English department into another world entirely.

DR: Did you ever consider getting married?

PS: Getting married? Yes, it's still on the agenda.

CW: Phillip would like to

PS: It became more pressing when I got ill.

CW: There wasn’t a lot of talk of marriage until …

PS: There was no possibility. Nobody could imagine gay marriage when we were younger.

CW: Yes, you see it was illegal. The gay marriage thing is really only about 15 years old or something. Prior to that, just coming out was a big deal. It was regarded as quite a radical step. A tiny little thing for me is that I was somewhat active in the gay liberation movement in Melbourne. At one stage gay teachers were asked, would they mind revealing themselves and standing on street corners. This sounds crazy – standing on street corners in Melbourne! Somehow I must have volunteered to stand on the street corner – it was Swanston and Collins – with a sign saying ‘I'm a gay teacher’.

DR: You’re joking, is there a photo of that?

CR: I swear, no one ever photographed me. I remember standing there alone. No one said offensive things and I think I could only hack it for about 40 minutes or something.

There was no negative stuff. So, the marriage thing didn't really come up until, well, when it came up – your memory is better than mine. And I didn't want to because it seemed to me to be stupid to mimic heterosexuals when heterosexuals were constantly showing us that marriage didn't work very well. And so, I just said to Phil, no, I don’t want to wear a ring saying I'm married to someone when it’s what a heterosexual would do. Now with Philip continuing to be sick, he wants to marry. I’m happy to, but I feel it's really hard to actually organise a serious marriage because you've got to … who do you not invite and who do you invite? I think that we would have to invite a huge number of people without hurting feelings. So, I find that quite a difficult thing. To me, the fact that our relationship is well over 40 years and will probably be into 50 years. That's enough to prove the strength of our relationship.

PS: In fact, if we had been able to get married back in the 70s or 80s, it would have made a huge difference to our sense of security, I think.

CW: We would have been more secure you mean?

PS: Yeah, I think so. But it wasn't ever a possibility. I mean, we weren't legal then, we were barely legal.

DR: What did that feel like, being illegal?

PS: It felt dreadful.

CW: But we just grew up with it, there was nothing else, you know.

PS: Yeah. There was a weird thing, a whole world of not being out, a whole repressed world. So many incredibly camp characters on the ABC who would never acknowledge themselves as homosexual.

CW: They were just ‘really happy’.

PS: Just very ‘cheerful’. So once you were out, you were confined to all the stereotypes that society could throw at you. There was also a kind of underground freedom, but I had one friend who was apprehended and forced to undergo weekly psychiatric counselling – this was when I was in Year 12 doing matriculation. He had to report to the police station each week. He had to attend a psychiatrist who used electro-convulsive therapy on him to get him attracted to … you know, he had to look at photographs. He was forced to undergo conversion therapy. His mother drove him to all the sessions. I had him as a living example right next to me – my best friend, who enjoyed literature and art like I did, and we were together on a lot of things. He had a criminal record as well, just to add to it all. Dreadful, really dreadful. There were all sorts of joys because you were young and you had a lot of energy and you felt fantastic and the world was incredibly, unbearably sexy, but at the same time, there was fear running throughout the whole thing.

DR: Did you ever experience any harassment or homophobia?

CW: I didn't actually, and I'm surprised to be able to say that. I think sometimes you realised in the early days that people were slightly tense about you, but they didn't express anything negative.

PS: No, I didn't experience anything very direct.

CW: But we lived in a world which was similar to our own middle class, polite world. And women were accepting of gay men quite early. Certainly, the women we knew were all quite warm towards us and they knew we were gay.

PS: The most intense homophobia I've experienced was a family matter.

CW: My brother was wonderful. I came out to him very early on. He said he didn't mind, instantly.

PS: He was remarkably mature and spoke to both of us. And I had the support of my other brother. But Bill simply wasn't able to ever express anything really. Mum and dad would never have coped with the idea that they had given rise to two homosexuals ...

DR: But they knew?

PS: They did know. They knew but they didn’t like it.

CW: When I came out to mine, they said ‘we know’.

DR: And how do you feel here in Castlemaine?

PS: I feel totally safe here.

CW Yeah, it's a lovely community.

PS: We've not met with the slightest negativity anywhere.

CW: I don't think so.

PS: We're very fortunate. Even you know some of our older more conservative neighbours, they’re still completely open and friendly, they just acknowledge us as a couple. They are good.

DR: Can you talk about ‘Queer’ and how that's been adopted by the younger generation?

PS: There's a friend of ours, she's a doctor, and she doesn't like the term ‘queer’ because for her generation, it's pejorative. It's got a negative connotation – you are perverse, you are queer, you're not mainstream, you're not straight. And she prefers to be known as a gay woman, not as queer. But I suppose in so many ways, people are looking for a broader definition of life really, and gay is more confining. I sort of share her point of view, I don't quite like queer I don't want to be known as odd or eccentric in some sort of weird way. That's what that term says for me. I’d prefer to be a gay person.

CW: A few weeks ago, I got on a train. It was an advertising train – you know how they take a whole carriage as an advertisement? And it had the word ‘QUEER’ – in letters this high, just ‘QUEER’. I thought it was wonderful, a wonderful moment. I almost laughed out loud. I think of the idea of this, compared to say 10 years ago, when it wouldn't have happened. It was a queer carriage full of straight people who didn’t care what carriage they were travelling in.

DR: Yeah, it was a great exhibition

CW: Yeah, it was. Now, would you like some soup and stay for lunch?